Environment...

Silting, Flooding, and Dredging

|

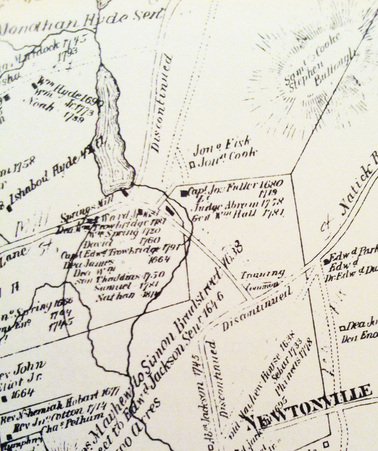

In colonial Newton in 1664, a man named John Spring built a dam on Smelt Brook to provide water power for his grist mill. A large pond, later known as Bullough’s Pond, formed behind the dam. For more that two centuries, Spring and his descendants operated the grist mill, which means that water flowed vigorously enough through the pond to power the mill. There were no paved roads near the pond during those two centuries and no storm drains. Rainwater could soak into the ground rather than becoming run-off into the pond. It’s reasonable to assume that far less silt ended up in the pond than is the case today. The grist mill fell into disuse in the late 19th century, and was burned down by vandals in 1886. |

|

Newtonville was rapidly developing at that time, with construction of houses and trolley lines near the pond. The pond began to silt up. The photo (left) shows trolley tracks crossing at the intersection of Commonwealth Avenue and Walnut Street. The Newton Land and Improvement Company, a real estate development enterprise, restored the pond and sold lots for houses to be constructed around it. In 1897, the company gave the pond to the City of Newton. |

|

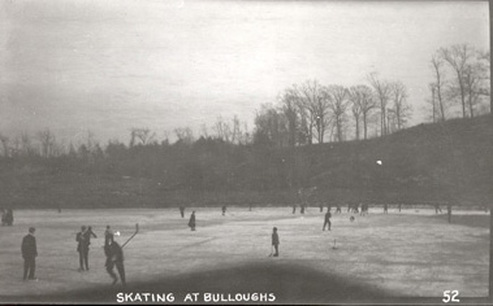

Shortly after 1910, the City began to promote ice skating on the pond (photo, right). Skating there became tremendously popular. As Newtonville was more and more built up, the pond began to silt up again, but the City committed to saving Bullough’s Pond as a recreational spot for residents. |

The City continued to maintain the pond and its banks, and prevented silting that would interfere with safe skating ice formation for decades. Betsy and Bill Leitch, the founders of the Bullough's Pond Association, moved to Newtonville in 1968. In the early 1980s Betsy noticed the deteriorating condition of Bullough’s Pond. The pond was becoming overgrown, shallow, and turning into a swamp. Betsy and Bill founded the BPA to raise awareness about the condition of the pond, and to lobby for a much-needed dredging and clean up. The two photos to below, both taken from Dexter Road, show how the pond filled in and became increasingly overgrown from 1981 (below left) to 1989 (below right).

|

By 1990, the Bullough's Pond Association was able to document that the pond was only a few feet deep in many spots. The photo (left) shows Betsy Leitch taking measurements. A drain down in advance of predicted heavy rain in 1990 revealed that islands of silt had formed where storm drain pipes opened into the center of the pond (below, left). Nutrient-laden run-off into the pond had, by 1990, fed the growth of a thick layer of algae and duckweed on the pond’s surface (below, right). |

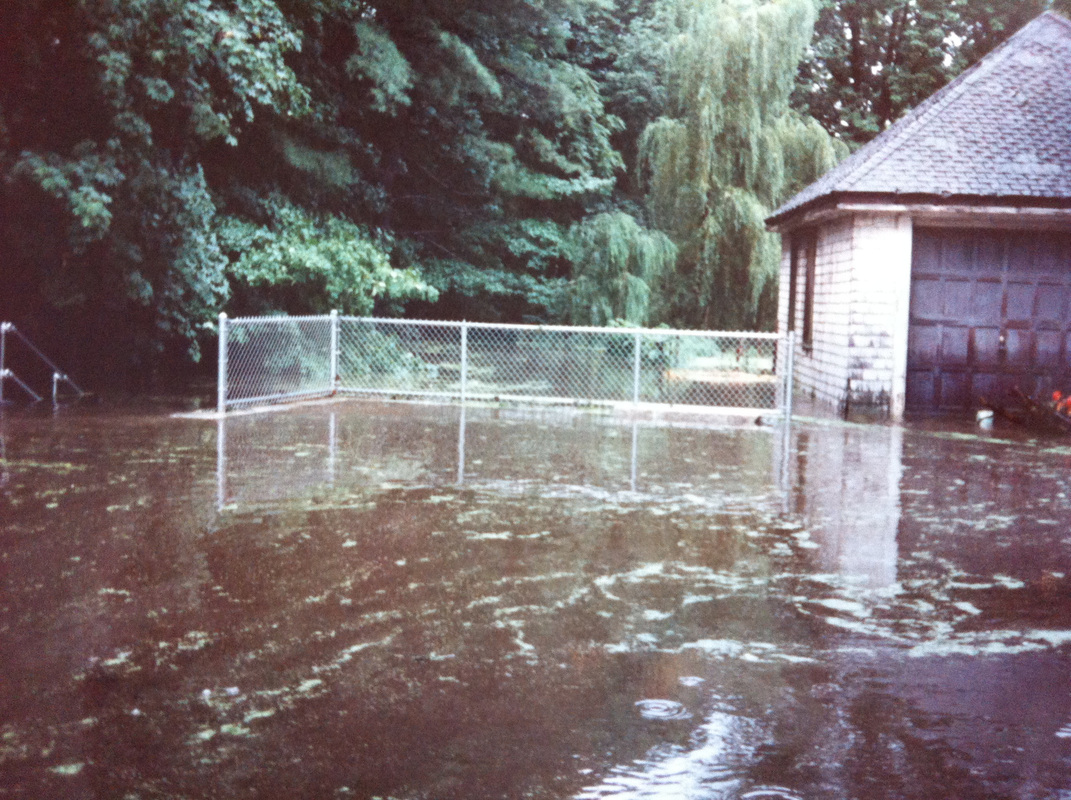

In 1990, the shallow, silted-up, swampy and overgrown condition of Bullough’s Pond made it a smelly eyesore and a breeding ground for mosquitoes. It also rendered the pond inadequate for its role as part of the City’s storm drainage system. That year, three heavy rainstorms struck Newton on July 25, August 11 and October 13. Bullough’s Pond was, by this point, too shallow to hold the extra water. The result was severe flooding in Newtonville, with damage to homes and to the Newton North High School campus.

On July 25, 1990, floodwaters from the pond poured into Laundry Brook and rose up over the top of the Hull Street culvert to deposit debris at this home (below left). The floodwaters swept the thick algae and duckweed mat from the surface of Bullough’s Pond and carried it downstream into Laundry Brook. Some of it was deposited on the collapsed fencing of a backyard garden destroyed by the flood (below right).

On July 25, 1990, floodwaters from the pond poured into Laundry Brook and rose up over the top of the Hull Street culvert to deposit debris at this home (below left). The floodwaters swept the thick algae and duckweed mat from the surface of Bullough’s Pond and carried it downstream into Laundry Brook. Some of it was deposited on the collapsed fencing of a backyard garden destroyed by the flood (below right).

On August 11, a second storm flooded Bullough’s Pond and Laundry Brook. Algae floated downstream as the waters submerged the Hull Street culvert (below, left). The duckweed mat on the surface of the pond, which had been holding the floodwaters back, ripped open (below, right), and water poured out of the pond into Laundry Brook.

|

The flood poured over Hull Street into the tennis courts at Newton North, 3:00 PM (below left), and had filled Hull Street by 4:00 PM (below right).

|

Ten minutes later, the waters had risen about three feet higher near the Hull Street culvert (left), flooding homes in Hull Street (below). |

The floodwaters next flowed into Walnut Street. The photos above show the flooding at the intersection of Walnut and Elm at 4:00 PM (above, left), and at Walnut and Cabot at about the same time (above right). The photo (below, left ) shows the floodwaters in Cabot Street, near Walnut at 4:15 PM. The City Hall ponds (below, right) also flooded on the same afternoon.

|

With forecasts of a third big storm imminent, the City drained the pond completely on October 13, 1990, revealing large amounts of green vegetative material on the pond's bottom (left). Despite the drain down, once the valve was closed, the pond began to fill up again. The rain came down heavily.

The rain fell all night and the pond was too shallow to hold it all. The pond flooded into Laundry Brook for a third time, this time resulting in major damage to the tennis courts and playing fields at Newton North (below, left and right). The three destructive floods of 1990 made many more people in Newton aware of the importance of Bullough’s Pond as a crucial part of the city’s storm drainage system, as well as, its importance as an historical, environmental and recreational asset. In 1992, plans and funding were finalized to dredge the pond and improve culverts for Laundry Brook. Dredging took place in early 1993 (left).

|

According to the City of Newton Recreation and Open Space Plan 2013-2017:

Most of Newton's water bodies receive some pollution from street drainage, over-fertilization from lawns and golf course fairways, road salt from winter operations and organic matter including pet wastes. Ponds and streams are rapidly filling in with sediment from street drains which need cleaning more often than the budget allows. In addition, aquatic plants grow quickly due to nutrient-laden runoff. While the removal of sediment and aquatic plants is extremely expensive, without it some ponds are vulnerable to filling in and disappearing. Removal of sediment from brooks is ongoing as a flood control measure, but wildlife habitat loss can result if the clearing is not carefully planned. Newton needs to develop a plan to ensure the water quality of these ponds and streams in order to maintain the quality of wildlife habitat, and the visual quality of these natural resources. (Sec. 4, pg. 12.)

Most of Newton's water bodies receive some pollution from street drainage, over-fertilization from lawns and golf course fairways, road salt from winter operations and organic matter including pet wastes. Ponds and streams are rapidly filling in with sediment from street drains which need cleaning more often than the budget allows. In addition, aquatic plants grow quickly due to nutrient-laden runoff. While the removal of sediment and aquatic plants is extremely expensive, without it some ponds are vulnerable to filling in and disappearing. Removal of sediment from brooks is ongoing as a flood control measure, but wildlife habitat loss can result if the clearing is not carefully planned. Newton needs to develop a plan to ensure the water quality of these ponds and streams in order to maintain the quality of wildlife habitat, and the visual quality of these natural resources. (Sec. 4, pg. 12.)